[Editor Note: This MPEP section has limited applicability to applications subject to examination under the first inventor to file (FITF) provisions of the AIA as set forth in 35 U.S.C. 100 (note). See MPEP § 2159 et seq. to determine whether an application is subject to examination under the FITF provisions, MPEP § 2159.03 for the conditions under which this section applies to an AIA application, and MPEP § 2150 et seq. for examination of applications subject to those provisions.]

A person shall be entitled to a patent unless -

Pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. 102(g) bars the issuance of a patent where another made the invention in the United States before the inventor and had not abandoned, suppressed, or concealed it. This section of pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. 102 forms a basis for interference practice. See MPEP Chapter 2300 for more information on interference procedure. See below and MPEP §§ 2138.01-2138.06 for more information on the requirements of pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. 102(g).

Pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. 102(g) issues such as conception, reduction to practice and diligence, while more commonly applied to interference matters, also arise in other contexts.

Pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. 102(g) may form the basis for an ex parte rejection if: (1) the subject matter at issue has been actually reduced to practice by another before the inventor’s invention; and (2) there has been no abandonment, suppression or concealment. See, e.g., Amgen, Inc. v. Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., 927 F.2d 1200, 1205, 18 USPQ2d 1016, 1020 (Fed. Cir. 1991); New Idea Farm Equipment Corp. v. Sperry Corp., 916 F.2d 1561, 1566, 16 USPQ2d 1424, 1428 (Fed. Cir. 1990); E.I. DuPont de Nemours & Co. v. Phillips Petroleum Co., 849 F.2d 1430, 1434, 7 USPQ2d 1129, 1132 (Fed. Cir. 1988); Kimberly-Clark v. Johnson & Johnson, 745 F.2d 1437, 1444-46, 223 USPQ 603, 606-08 (Fed. Cir. 1984). To qualify as prior art under pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. 102(g), however, there must be evidence that the subject matter was actually reduced to practice, in that conception alone is not sufficient. See Kimberly-Clark, 745 F.2d at 1445, 223 USPQ at 607. While the filing of an application for patent is a constructive reduction to practice, the filing of an application does not in itself provide the evidence necessary to show an actual reduction to practice of any of the subject matter disclosed in the application as is necessary to provide the basis for an ex parte rejection under pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. 102(g). Thus, absent evidence showing an actual reduction to practice (which is generally not available during ex parte examination), the disclosure of a United States patent application publication or patent falls under pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. 102(e) and not under pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. 102(g). Cf.In re Zletz, 893 F.2d 319, 323, 13 USPQ2d 1320, 1323 (Fed. Cir. 1989) (the disclosure in a reference United States patent does not fall under pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. 102(g) but under pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. 102(e)).

In addition, subject matter qualifying as prior art only under pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. 102(g) may also be the basis for an ex parte rejection under pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. 103. See In re Bass, 474 F.2d 1276, 1283, 177 USPQ 178, 183 (CCPA 1973) (in an unsuccessful attempt to utilize a 37 CFR 1.131 affidavit relating to a combination application, the inventors admitted that the subcombination screen of a copending application which issued as a patent was earlier conceived than the combination). Pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. 103(c), however, states that subsection (g) of pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. 102 will not preclude patentability where subject matter developed by another person, that would otherwise qualify under pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. 102(g), and the claimed invention of an application under examination were owned by the same person, subject to an obligation of assignment to the same person, or involved in a joint research agreement, which meets the requirements of pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. 103(c)(2) and (c)(3), at the time the invention was made. See MPEP § 2146.

For additional examples of pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. 102(g) issues such as conception, reduction to practice and diligence outside the context of interference matters, see In re Costello, 717 F.2d 1346, 219 USPQ 389 (Fed. Cir. 1983) (discussing the concepts of conception and constructive reduction to practice in the context of a declaration under 37 CFR 1.131), and Kawai v. Metlesics, 480 F.2d 880, 178 USPQ 158 (CCPA 1973) (holding constructive reduction to practice for foreign priority under 35 U.S.C. 119 requires meeting the requirements of 35 U.S.C. 101 and 35 U.S.C. 112).

[Editor Note: This MPEP section has limited applicability to applications subject to examination under the first inventor to file (FITF) provisions of the AIA as set forth in 35 U.S.C. 100 (note). See MPEP § 2159 et seq. to determine whether an application is subject to examination under the FITF provisions, MPEP § 2159.03 for the conditions under which this section applies to an AIA application, and MPEP § 2150 et seq. for examination of applications subject to those provisions.]

I. PRE-AIA 35 U.S.C. 102(g) IS THE BASIS OF INTERFERENCE PRACTICE

Subsection (g) of pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. 102 is the basis of interference practice for determining priority of invention between two parties. See Bigham v. Godtfredsen, 857 F.2d 1415, 1416, 8 USPQ2d 1266, 1267 (Fed. Cir. 1988), 35 U.S.C. 135, 37 CFR Part 41, Subparts D and E and MPEP Chapter 2300. An interference is an inter partes proceeding directed at determining the first to invent as among the parties to the proceeding, involving two or more pending applications naming different inventors or one or more pending applications and one or more unexpired patents naming different inventors. The United States is unusual in having a first to invent rather than a first to file system in certain applications. Paulik v. Rizkalla, 760 F.2d 1270, 1272, 226 USPQ 224, 225 (Fed. Cir. 1985) (reviews the legislative history of the subsection in a concurring opinion by Judge Rich). The first of many to reduce an invention to practice around the same time will be the sole party to obtain a patent in some instances, Radio Corp. of Americav.Radio Eng’g Labs., Inc., 293 U.S. 1, 2, 21 USPQ 353, 353-4 (1934), unless another was the first to conceive and couple a later-in-time reduction to practice with diligence from a time just prior to when the second conceiver entered the field to the first conceiver’s reduction to practice. Hull v. Davenport, 90 F.2d 103, 105, 33 USPQ 506, 508 (CCPA 1937). See the priority time charts below illustrating this point. Upon conclusion of an interference, subject matter claimed by the losing party that was the basis of the interference is rejected under pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. 102(g), unless the acts showing prior invention were not in this country.

It is noted that 35 U.S.C. 101 requires that whoever invents or discovers the claimed invention is the party that must be named as the inventor before a parent may be granted. Where it can be shown that a named inventor has “derived” an invention from another, a rejection under pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. 102(f) is proper if applicable. Ex parte Kusko, 215 USPQ 972, 974 (Bd. App. 1981) (“most, if not all, determinations under [pre-AIA] Section 102(f) involve the question of whether one party derived an invention from another”); Price v. Symsek, 988 F.2d 1187, 1190, 26 USPQ2d 1031, 1033 (Fed. Cir. 1993) (Although derivation and priority of invention both focus on inventorship, derivation addresses originality, i.e., who invented the subject matter, whereas priority focuses on which party invented the subject matter first.).

II. PRIORITY TIME CHARTS

The following priority time charts illustrate the award of invention priority in several situations. The time charts apply to interference proceedings and are also applicable to declarations or affidavits filed under 37 CFR 1.131 to antedate references which are available as prior art under pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. 102(a) or 102(e). Note, however, in the context of 37 CFR 1.131, an inventor does not have to show that the invention was not abandoned, suppressed, or concealed from the time of an actual reduction to practice to a constructive reduction to practice because the length of time taken to file a patent application after an actual reduction to practice is generally of no consequence except in an interference proceeding. Paulik v. Rizkalla, 760 F.2d 1270, 226 USPQ 224 (Fed. Cir. 1985). See the discussion of abandonment, suppression, and concealment in MPEP § 2138.03.

For purposes of analysis under 37 CFR 1.131, the conception and reduction to practice of the reference to be antedated are both considered to be on the effective filing date of domestic patent or foreign patent or the date of printed publication.

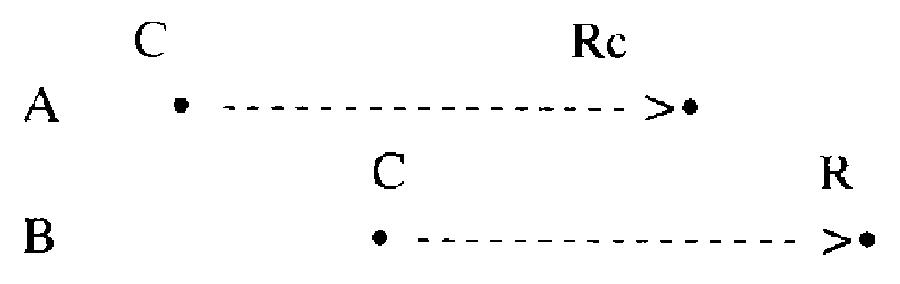

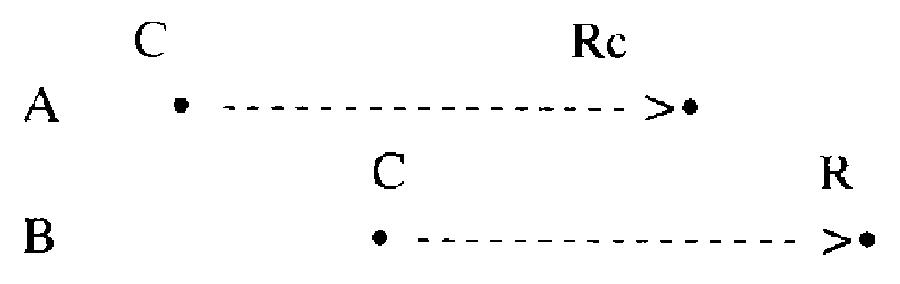

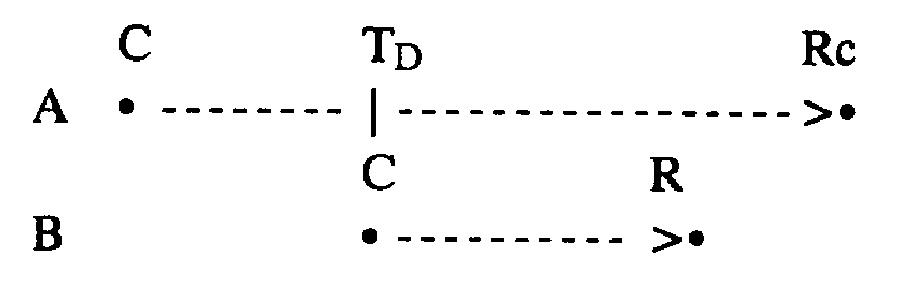

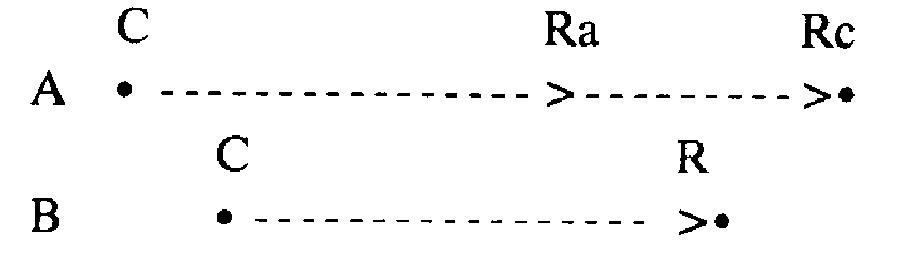

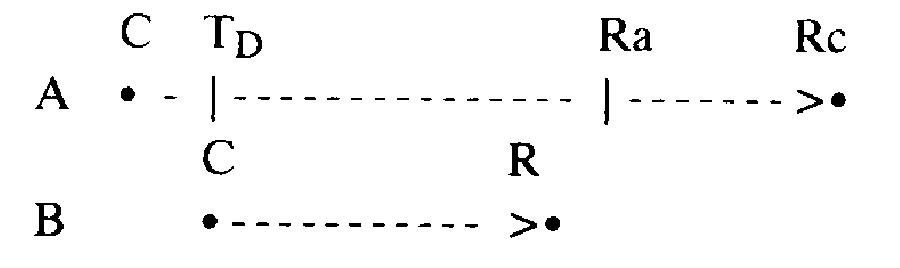

In the charts, C = conception, R = reduction to practice (either actual or constructive), Ra = actual reduction to practice, Rc = constructive reduction to practice, and TD = commencement of diligence.

Example 1

A is awarded priority in an interference, or antedates B as a reference in the context of a declaration or affidavit filed under 37 CFR 1.131, because A conceived the invention before B and constructively reduced the invention to practice before B reduced the invention to practice. The same result would be reached if the conception date was the same for both inventors A and B.

Example 2

A is awarded priority in an interference, or antedates B as a reference in the context of a declaration or affidavit filed under 37 CFR 1.131, if A can show reasonable diligence from TD (a point just prior to B’s conception) until Rc because A conceived the invention before B, and diligently constructively reduced the invention to practice even though this was after B reduced the invention to practice.

Example 3

A is awarded priority in an interference in the absence of abandonment, suppression, or concealment from Ra to Rc, because A conceived the invention before B, actually reduced the invention to practice before B reduced the invention to practice, and did not abandon, suppress, or conceal the invention after actually reducing the invention to practice and before constructively reducing the invention to practice.

A antedates B as a reference in the context of a declaration or affidavit filed under 37 CFR 1.131 because A conceived the invention before B and actually reduced the invention to practice before B reduced the invention to practice.

Example 4

A is awarded priority in an interference if A can show reasonable diligence from TD (a point just prior to B’s conception) until Ra in the absence of abandonment, suppression, or concealment from Ra to Rc, because A conceived the invention before B, diligently actually reduced the invention to practice (after B reduced the invention to practice), and did not abandon, suppress, or conceal the invention after actually reducing the invention to practice and before constructively reducing the invention to practice.

A antedates B as a reference in the context of a declaration or affidavit filed under 37 CFR 1.131 because A conceived the invention before B, and diligently actually reduced the invention to practice, even though this was after B reduced the invention to practice.

III. 37 CFR 1.131 DOES NOT APPLY IN INTERFERENCE PROCEEDINGSInterference practice operates to the exclusion of ex parte practice under 37 CFR 1.131 which permits an inventor to show an actual date of invention prior to the effective date of a reference or activity applied under pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. 102 or 103, as long as the reference is not a statutory bar under pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. 102(b) or a U.S. patent application publication claiming the same patentable invention. Ex parte Standish, 10 USPQ2d 1454, 1457 (Bd. Pat. App. & Inter. 1988) (An application claim to the “same patentable invention” claimed in a domestic patent requires interference rather than an affidavit under 37 CFR 1.131 to antedate the patent. The term “same patentable invention” encompasses a claim that is either anticipated by or obvious in view of the subject matter recited in the patent claim.). Subject matter which is prior art under pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. 102(g) and is subject to an interference is not open to further inquiry under 37 CFR 1.131 during the interference proceeding.

IV. LOST COUNTS IN AN INTERFERENCE ARE NOT, PER SE, STATUTORY PRIOR ART

Loss of an interference count alone does not make its subject matter statutory prior art to losing party; however, lost count subject matter that is available as prior art under 35 U.S.C. 102 may be used alone or in combination with other references under 35 U.S.C. 103. But see In re Deckler, 977 F.2d 1449, 24 USPQ2d 1448 (Fed. Cir. 1992) (Under the principles of res judicata and collateral estoppel, Deckler was not entitled to claims that were patentably indistinguishable from the claim lost in interference even though the subject matter of the lost count was not available for use in an obviousness rejection under 35 U.S.C. 103.).

[Editor Note: This MPEP section has limited applicability to applications subject to examination under the first inventor to file (FITF) provisions of the AIA as set forth in 35 U.S.C. 100 (note). See MPEP § 2159 et seq. to determine whether an application is subject to examination under the FITF provisions, MPEP § 2159.03 for the conditions under which this section applies to an AIA application, and MPEP § 2150 et seq. for examination of applications subject to those provisions.]

An invention is made when there is a conception and a reduction to practice. Dunn v. Ragin, 50 USPQ 472, 474 (Bd. Pat. Inter. 1941). Prior art under pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. 102(g) is limited to an invention that is made. In re Katz, 687 F.2d 450, 454, 215 USPQ 14, 17 (CCPA 1982) (the publication of an article, alone, is not deemed a constructive reduction to practice, and therefore its disclosure does not prove that any invention within the meaning of pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. 102(g) has ever been made).

Subject matter under pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. 102(g) is available only if made in this country. Pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. 104. Kondo v. Martel, 220 USPQ 47 (Bd. Pat. Inter. 1983) (acts of conception, reduction to practice and diligence must be demonstrated in this country). Compare Colbert v. Lofdahl, 21 USPQ2d 1068, 1071 (Bd. Pat. App. & Inter. 1991) (“[i]f the invention is reduced to practice in a foreign country and knowledge of the invention was brought into this country and disclosed to others, the inventor can derive no benefit from the work done abroad and such knowledge is merely evidence of conception of the invention”).

In accordance with pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. 102(g)(1), a party involved in an interference proceeding under pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. 135 or 291 may establish a date of invention under pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. 104. Pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. 104, as amended by GATT (Public Law 103-465, 108 Stat. 4809 (1994)) and NAFTA (Public Law 103-182, 107 Stat. 2057 (1993)), provides that an inventor can establish a date of invention in a NAFTA member country on or after December 8, 1993 or in WTO member country other than a NAFTA member country on or after January 1, 1996. Accordingly, an interference count may be won or lost on the basis of establishment of invention by one of the parties in a NAFTA or WTO member country, thereby rendering the subject matter of that count unpatentable to the other party under the principles of res judicata and collateral estoppel, even though such subject matter is not available as statutory prior art under pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. 102(g). See MPEP § 2138.01 regarding lost interference counts which are not statutory prior art.

[Editor Note: This MPEP section has limited applicability to applications subject to examination under the first inventor to file (FITF) provisions of the AIA as set forth in 35 U.S.C. 100 (note). See MPEP § 2159 et seq. to determine whether an application is subject to examination under the FITF provisions, MPEP § 2159.03 for the conditions under which this section applies to an AIA application, and MPEP § 2150 et seq. for examination of applications subject to those provisions.]

Pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. 102(g) generally makes available as prior art within the meaning of 35 U.S.C. 103, the prior invention of another who has not abandoned, suppressed or concealed it. In re Bass, 474 F.2d 1276, 177 USPQ 178 (CCPA 1973); In re Suska, 589 F.2d 527, 200 USPQ 497 (CCPA 1979) (The result of applying the suppression and concealment doctrine is that the inventor who did not conceal (but was the de facto last inventor) is treated legally as the first to invent, while the de facto first inventor who suppressed or concealed is treated as a later inventor. The de facto first inventor, by his suppression and concealment, lost the right to rely on his actual date of invention not only for priority purposes, but also for purposes of avoiding the invention of the counts as prior art.).

“The courts have consistently held that an invention, though completed, is deemed abandoned, suppressed, or concealed if, within a reasonable time after completion, no steps are taken to make the invention publicly known. Thus failure to file a patent application; to describe the invention in a publicly disseminated document; or to use the invention publicly, have been held to constitute abandonment, suppression, or concealment.” Correge v. Murphy, 705 F.2d 1326, 1330, 217 USPQ 753, 756 (Fed. Cir. 1983) (quoting International Glass Co.v.United States, 408 F.2d 395, 403, 159 USPQ 434, 441 (Ct. Cl. 1968)). In Correge, an invention was actually reduced to practice, 7 months later there was a public disclosure of the invention, and 8 months thereafter a patent application was filed. The court held filing a patent application within 1 year of a public disclosure is not an unreasonable delay, therefore reasonable diligence must only be shown between the date of the actual reduction to practice and the public disclosure to avoid the inference of abandonment.

I. DURING AN INTERFERENCE PROCEEDING, AN INFERENCE OF SUPPRESSION OR CONCEALMENT MAY ARISE FROM DELAY IN FILING PATENT APPLICATION

Once an invention is actually reduced to practice an inventor need not rush to file a patent application. Shindelar v. Holdeman, 628 F.2d 1337, 1341, 207 USPQ 112, 116 (CCPA 1980). The length of time taken to file a patent application after an actual reduction to practice is generally of no consequence except in an interference proceeding. Paulik v. Rizkalla, 760 F.2d 1270, 1271, 226 USPQ 225, 226 (Fed. Cir. 1985) (suppression or concealment may be deliberate or may arise due to an inference from a “too long” delay in filing a patent application). Peeler v. Miller, 535 F.2d 647, 656, 190 USPQ 117,124 (CCPA 1976) (“mere delay, without more, is not sufficient to establish suppression or concealment.” “What we are deciding here is that Monsanto’s delay is not ‘merely delay’ and that Monsanto's justification for the delay is inadequate to overcome the inference of suppression created by the excessive delay.” The word “mere” does not imply a total absence of a limit on the duration of delay. Whether any delay is “mere” is decided only on a case-by-case basis.).

Where a junior party in an interference relies upon an actual reduction to practice to demonstrate first inventorship, and where the hiatus in time between the date for the junior party's asserted reduction to practice and the filing of its application is unreasonably long, the hiatus may give rise to an inference that the junior party in fact suppressed or concealed the invention and the junior party will not be allowed to rely upon the earlier actual reduction to practice. Young v. Dworkin, 489 F.2d 1277, 1280 n.3, 180 USPQ 388, 391 n.3 (CCPA 1974) (suppression and concealment issues are to be addressed on a case-by-case basis).

II. SUPPRESSION OR CONCEALMENT NEED NOT BE ATTRIBUTED TO INVENTOR

Suppression or concealment need not be attributed to the inventor. Peeler v. Miller, 535 F.2d 647, 653-54, 190 USPQ 117, 122 (CCPA 1976) (“four year delay from the time an inventor … completes his work … and the time his assignee-employer files a patent application is, prima facie, unreasonably long in an interference with a party who filed first”); Shindelar v. Holdeman, 628 F.2d 1337, 1341-42, 207 USPQ 112, 116-17 (CCPA 1980) (A patent attorney’s workload will not preclude a holding of an unreasonable delay— the court identified that a total of 3 months was possibly excusable in regard to the filing of an application.).

III. INFERENCE OF SUPPRESSION OR CONCEALMENT IS REBUTTABLE

Notwithstanding an inference of suppression or concealment due to time(s) of inactivity after reduction to practice, the senior party may still prevail if the senior party shows renewed activity on the invention that is just prior to the junior party’s entry into field coupled with the diligent filing of an application. Lutzkerv.Plet, 843 F.2d 1364, 1367-69, 6 USPQ2d 1370, 1371-72 (Fed. Cir. 1988) (activities directed towards commercialization not sufficient to rebut inference); Holmwood v. Cherpeck, 2 USPQ2d 1942, 1945 (Bd. Pat. App. & Inter. 1986) (the inference of suppression or concealment may be rebutted by showing activity directed to perfecting the invention, preparing the application, or preparing other compounds within the scope of the generic invention); Engelhardt v. Judd, 369 F.2d 408, 411, 151 USPQ 732, 735 (CCPA 1966) (“We recognize that an inventor of a new series of compounds should not be forced to file applications piecemeal on each new member as it is synthesized, identified and tested for utility. A reasonable amount of time should be allowed for completion of the research project on the whole series of new compounds, and a further reasonable time period should then be allowed for drafting and filing the patent application(s) thereon.”); Bogoslowskyv.Huse, 142 F.2d 75, 77, 61 USPQ 349, 351 (CCPA 1944) (The doctrine of suppression and concealment is not applicable to conception without an actual reduction to practice.).

IV. ABANDONMENT

A finding of suppression or concealment may not amount to a finding of abandonment wherein a right to a patent is lost. Steierman v. Connelly, 197 USPQ 288, 289 (Comm'r Pat. 1976); Correge v. Murphy, 705 F.2d 1326, 1329, 217 USPQ 753, 755 (Fed. Cir. 1983) (an invention cannot be abandoned until it is first reduced to practice).

[Editor Note: This MPEP section has limited applicability to applications subject to examination under the first inventor to file (FITF) provisions of the AIA as set forth in 35 U.S.C. 100 (note). See MPEP § 2159 et seq. to determine whether an application is subject to examination under the FITF provisions, MPEP § 2159.03 for the conditions under which this section applies to an AIA application, and MPEP § 2150 et seq. for examination of applications subject to those provisions.]

Conception has been defined as “the complete performance of the mental part of the inventive act” and it is “the formation in the mind of the inventor of a definite and permanent idea of the complete and operative invention as it is thereafter to be applied in practice….” Townsend v. Smith, 36 F.2d 292, 295, 4 USPQ 269, 271 (CCPA 1929). “[C]onception is established when the invention is made sufficiently clear to enable one skilled in the art to reduce it to practice without the exercise of extensive experimentation or the exercise of inventive skill.” Hiatt v. Ziegler, 179 USPQ 757, 763 (Bd. Pat. Inter. 1973). Conception has also been defined as a disclosure of an invention which enables one skilled in the art to reduce the invention to a practical form without “exercise of the inventive faculty.” Gunter v. Stream, 573 F.2d 77, 197 USPQ 482 (CCPA 1978). See also Coleman v. Dines, 754 F.2d 353, 224 USPQ 857 (Fed. Cir. 1985) (It is settled that in establishing conception a party must show possession of every feature recited in the count, and that every limitation of the count must have been known to the inventor at the time of the alleged conception. Conception must be proved by corroborating evidence.); Hybritech Inc. v. Monoclonal Antibodies Inc., 802 F. 2d 1367, 1376, 231 USPQ 81, 87 (Fed. Cir. 1986) (Conception is the “formation in the mind of the inventor, of a definite and permanent idea of the complete and operative invention, as it is hereafter to be applied in practice.”); Hitzeman v. Rutter, 243 F.3d 1345, 58 USPQ2d 1161 (Fed. Cir. 2001) (Inventor’s “hope” that a genetically altered yeast would produce antigen particles having the particle size and sedimentation rates recited in the claims did not establish conception, since the inventor did not show that he had a “definite and permanent understanding” as to whether or how, or a reasonable expectation that, the yeast would produce the recited antigen particles.); Staehelin v. Secher, 24 USPQ2d 1513, 1522 (Bd. Pat. App. & Inter. 1992) (“evidence of conception naming only one of the actual inventive entity inures to the benefit of and serves as evidence of conception by the complete inventive entity”).

I. CONCEPTION MUST BE DONE IN THE MIND OF THE INVENTOR

The inventor must form a definite and permanent idea of the complete and operable invention to establish conception. Bosies v. Benedict, 27 F.3d 539, 543, 30 USPQ2d 1862, 1865 (Fed. Cir. 1994) (Testimony by a noninventor as to the meaning of a variable of a generic compound described in an inventor’s notebook was insufficient as a matter of law to establish the meaning of the variable because the testimony was not probative of what the inventors conceived.). A person who shares in the conception of a claimed invention is a joint inventor of that invention. In re VerHoef, 888 F.3d 1362, 1366-67, 126 F.2d 1561, 1564-65 (Fed. Cir. 2018).

II. CONCEPTION REQUIRES CONTEMPORANEOUS RECOGNITION AND APPRECIATION OF THE INVENTION

There must be a contemporaneous recognition and appreciation of the invention for there to be conception. Silvestri v. Grant, 496 F.2d 593, 596, 181 USPQ 706, 708 (CCPA 1974) (“an accidental and unappreciated duplication of an invention does not defeat the patent right of one who, though later in time was the first to recognize that which constitutes the inventive subject matter”); Invitrogen,Corp. v. Clontech Laboratories, Inc., 429 F.3d 1052, 1064, 77 USPQ2d 1161, 1169 (Fed. Cir. 2005) (In situations where there is unrecognized accidental duplication, establishing conception requires evidence that the inventor actually made the invention and understood the invention to have the features that comprise the inventive subject matter at issue).Langer v. Kaufman, 465 F.2d 915, 918, 175 USPQ 172, 174 (CCPA 1972) (new form of catalyst was not recognized when it was first produced; conception cannot be established nunc pro tunc). However, an inventor does not need to know that the invention will work for there to be complete conception. Burroughs Wellcome Co. v. Barr Labs., Inc., 40 F.3d 1223, 1228, 32 USPQ2d 1915, 1919 (Fed. Cir. 1994) (Draft patent application disclosing treatment of AIDS with AZT reciting dosages, forms, and routes of administration was sufficient to collaborate conception whether or not the inventors believed the inventions would work based on initial screening tests.) Furthermore, the inventor does not need to appreciate the patentability of the invention. Dow Chem. Co. v. Astro-Valcour, Inc., 267 F.3d 1334, 1341, 60 USPQ2d 1519, 1523 (Fed. Cir. 2001).

The first to conceive of a species is not necessarily the first to conceive of the generic invention. In re Jolley, 308 F.3d 1317, 1323 n.2, 64 USPQ2d 1901, 1905 n.2 (Fed. Cir. 2002). Further, while conception of a species within a genus may constitute conception of the genus, conception of one species and the genus may not constitute conception of another species in the genus. Oka v. Youssefyeh, 849 F.2d 581, 7 USPQ2d 1169 (Fed. Cir. 1988) (conception of a chemical requires both the idea of the structure of the chemical and possession of an operative method of making it). See also Amgen, Inc. v. Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., 927 F.2d 1200, 1206, 18 USPQ2d 1016, 1021 (Fed. Cir. 1991) (in the isolation of a gene, defining a gene by its principal biological property is not sufficient for conception absent an ability to envision the detailed constitution as well as a method for obtaining it); Fiers v. Revel, 984 F.2d 1164, 1170, 25 USPQ2d 1601, 1605 (Fed. Cir. 1993) (“[b]efore reduction to practice, conception only of a process for making a substance, without conception of a structural or equivalent definition of that substance, can at most constitute a conception of the substance claimed as a process” but cannot constitute conception of the substance; as “conception is not enablement,” conception of a purified DNA sequence coding for a specific protein by function and a method for its isolation that could be carried out by one of ordinary skill in the art is not conception of that material). See MPEP §§ 2106.04(b) and 2106.04(c) for information on the subject matter eligibility of inventions involving isolated genes.

On rare occasions conception and reduction to practice occur simultaneously in unpredictable technologies. Alpert v. Slatin, 305 F.2d 891, 894, 134 USPQ 296, 299 (CCPA 1962). “[I]n some unpredictable areas of chemistry and biology, there is no conception until the invention has been reduced to practice.” MacMillan v.Moffett, 432 F.2d 1237, 1234-40, 167 USPQ 550, 552-553 (CCPA 1970). See also Hitzeman v. Rutter, 243 F.3d 1345, 58 USPQ2d 1161 (Fed. Cir. 2001) (conception simultaneous with reduction to practice where appellant lacked reasonable certainty that yeast’s performance of certain intracellular processes would result in the claimed antigen particles); Dunn v. Ragin, 50 USPQ 472, 475 (Bd. Pat. Inter. 1941) (a new variety of asexually reproduced plant is conceived and reduced to practice when it is grown and recognized as a new variety). Under these circumstances, conception is not complete if subsequent experimentation reveals factual uncertainty which “so undermines the specificity of the inventor’s idea that it is not yet a definite and permanent reflection of the complete invention as it will be used in practice.” Burroughs Wellcome Co. v. Barr Labs., Inc., 40 F.3d 1223, 1229, 32 USPQ2d 1915, 1920 (Fed. Cir. 1994).

III. A PREVIOUSLY ABANDONED APPLICATION WHICH WAS NOT COPENDING WITH A SUBSEQUENT APPLICATION IS EVIDENCE ONLY OF CONCEPTION

An abandoned application with which no subsequent application was copending serves to abandon benefit of the application’s filing as a constructive reduction to practice and the abandoned application is evidence only of conception. In re Costello, 717 F.2d 1346, 1350, 219 USPQ 389, 392 (Fed. Cir. 1983).

[Editor Note: This MPEP section has limited applicability to applications subject to examination under the first inventor to file (FITF) provisions of the AIA as set forth in 35 U.S.C. 100 (note). See MPEP § 2159 et seq. to determine whether an application is subject to examination under the FITF provisions, MPEP § 2159.03 for the conditions under which this section applies to an AIA application, and MPEP § 2150 et seq. for examination of applications subject to those provisions.]

Reduction to practice may be an actual reduction or a constructive reduction to practice which occurs when a patent application on the claimed invention is filed. The filing of a patent application serves as conception and constructive reduction to practice of the subject matter described in the application. Thus the inventor need not provide evidence of either conception or actual reduction to practice when relying on the content of the patent application. Hyatt v. Boone, 146 F.3d 1348, 1352, 47 USPQ2d 1128, 1130 (Fed. Cir. 1998). A reduction to practice can be done by another on behalf of the inventor. De Solms v.Schoenwald, 15 USPQ2d 1507, 1510 (Bd. Pat. App. & Inter. 1990). “While the filing of the original application theoretically constituted a constructive reduction to practice at the time, the subsequent abandonment of that application also resulted in an abandonment of the benefit of that filing as a constructive reduction to practice. The filing of the original application is, however, evidence of conception of the invention.” In re Costello, 717 F.2d 1346, 1350, 219 USPQ 389, 392 (Fed. Cir. 1983)(The second application was not co-pending with the original application and it did not reference the original application. Because of the requirements of 35 U.S.C. 120 had not been satisfied, the filing of the original application was not recognized as constructive reduction to practice of the invention.).

I. CONSTRUCTIVE REDUCTION TO PRACTICE REQUIRES COMPLIANCE WITH 35 U.S.C. 112(a) or PRE-AIA 35 U.S.C. 112, FIRST PARAGRAPH

When a party to an interference seeks the benefit of an earlier-filed U.S. patent application, the earlier application must meet the requirements of 35 U.S.C. 120 and 35 U.S.C. 112(a) or pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. 112, first paragraph for the subject matter of the count. The earlier application must meet the enablement requirement and must contain a written description of the subject matter of the interference count. Hyatt v. Boone, 146 F.3d 1348, 1352, 47 USPQ2d 1128, 1130 (Fed. Cir. 1998). Proof of a constructive reduction to practice requires sufficient disclosure under the “how to use” and “how to make” requirements of 35 U.S.C. 112(a) or pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. 112, first paragraph. Kawai v. Metlesics, 480 F.2d 880, 886, 178 USPQ 158, 163 (CCPA 1973) (A constructive reduction to practice is not proven unless the specification discloses a practical utility where one would not be obvious. Prior art which disclosed an anticonvulsant compound which differed from the claimed compound only in the absence of a -CH2- group connecting two functional groups was not sufficient to establish utility of the claimed compound because the compounds were not so closely related that they could be presumed to have the same utility.). The purpose of the written description requirement is “to ensure that the inventor had possession, as of the filing date of the application relied on, of the specific subject matter later claimed by him.” In re Edwards, 568 F.2d 1349, 1351-52, 196 USPQ 465, 467 (CCPA 1978). The written description must include all of the limitations of the interference count, or the inventor must show that any absent text is necessarily comprehended in the description provided and would have been so understood at the time the patent application was filed. Furthermore, the written description must be sufficient, when the entire specification is considered, such that the “necessary and only reasonable construction” that would be given it by a person skilled in the art is one that clearly supports each positive limitation in the count. Hyatt v. Boone, 146 F.3d at 1354-55, 47 USPQ2d at 1130-1132 (Fed. Cir. 1998) (The claim could be read as describing subject matter other than that of the count and thus did not establish that the inventor was in possession of the invention of the count.). See also Bigham v. Godtfredsen, 857 F.2d 1415, 1417, 8 USPQ2d 1266, 1268 (Fed. Cir. 1988) (“[t]he generic term halogen comprehends a limited number of species, and ordinarily constitutes a sufficient written description of the common halogen species,” except where the halogen species are patentably distinct).

II. REQUIREMENTS TO ESTABLISH ACTUAL REDUCTION TO PRACTICE

“In an interference proceeding, a party seeking to establish an actual reduction to practice must satisfy a two-prong test: (1) the party constructed an embodiment or performed a process that met every element of the interference count, and (2) the embodiment or process operated for its intended purpose.” Eaton v. Evans, 204 F.3d 1094, 1097, 53 USPQ2d 1696, 1698 (Fed. Cir. 2000).

The same evidence sufficient for a constructive reduction to practice may be insufficient to establish an actual reduction to practice, which requires a showing of the invention in a physical or tangible form that shows every element of the count. Wetmore v. Quick, 536 F.2d 937, 942, 190 USPQ 223, 227 (CCPA 1976). For an actual reduction to practice, the invention must have been sufficiently tested to demonstrate that it will work for its intended purpose, but it need not be in a commercially satisfactory stage of development. See, e.g., Scott v. Finney, 34 F.3d 1058, 1062, 32 USPQ2d 1115, 1118-19 (Fed. Cir. 1994) (citing numerous cases wherein the character of the testing necessary to support an actual reduction to practice varied with the complexity of the invention and the problem it solved). If a device is so simple, and its purpose and efficacy so obvious, construction alone is sufficient to demonstrate workability. King Instrument Corp. v. Otari Corp., 767 F.2d 853, 860, 226 USPQ 402, 407 (Fed. Cir. 1985).

For additional cases pertaining to the requirements necessary to establish actual reduction to practice see DSL Dynamic Sciences, Ltd. v. Union Switch & Signal, Inc., 928 F.2d 1122, 1126, 18 USPQ2d 1152, 1155 (Fed. Cir. 1991) (“events occurring after an alleged actual reduction to practice can call into question whether reduction to practice has in fact occurred”); Fitzgerald v. Arbib, 268 F.2d 763, 765-66, 122 USPQ 530, 531-32 (CCPA 1959) (“the reduction to practice of a three-dimensional design invention requires the production of an article embodying that design” in “other than a mere drawing”); Birmingham v. Randall, 171 F.2d 957, 80 USPQ 371, 372 (CCPA 1948) (To establish an actual reduction to practice of an invention directed to a method of making a product, it is not enough to show that the method was performed. “[S]uch an invention is not reduced to practice until it is established that the product made by the process is satisfactory, and [ ] this may require successful testing of the product.”).

III. TESTING REQUIRED TO ESTABLISH AN ACTUAL REDUCTION TO PRACTICE

“The nature of testing which is required to establish a reduction to practice depends on the particular facts of each case, especially the nature of the invention.” Gellert v. Wanberg, 495 F.2d 779, 783, 181 USPQ 648, 652 (CCPA 1974) (“an invention may be tested sufficiently … where less than all of the conditions of actual use are duplicated by the tests”); Wells v. Fremont, 177 USPQ 22, 24-5 (Bd. Pat. Inter. 1972) (“even where tests are conducted under ‘bench’ or laboratory conditions, those conditions must ‘fully duplicate each and every condition of actual use’ or if they do not, then the evidence must establish a relationship between the subject matter, the test condition and the intended functional setting of the invention,” but it is not required that all the conditions of all actual uses be duplicated, such as rain, snow, mud, dust and submersion in water).

IV. REDUCTION TO PRACTICE REQUIRES RECOGNITION AND APPRECIATION OF THE INVENTION

The invention must be recognized and appreciated for a reduction to practice to occur. “The rule that conception and reduction to practice cannot be established nunc pro tunc simply requires that in order for an experiment to constitute an actual reduction to practice, there must have been contemporaneous appreciation of the invention at issue by the inventor…. Subsequent testing or later recognition may not be used to show that a party had contemporaneous appreciation of the invention. However, evidence of subsequent testing may be admitted for the purpose of showing that an embodiment was produced and that it met the limitations of the count.” Cooper v. Goldfarb, 154 F.3d 1321, 1331, 47 USPQ2d 1896, 1904 (Fed. Cir. 1998) (citations omitted). Meitzner v. Corte, 537 F.2d 524, 528, 190 USPQ 407, 410 (CCPA 1976) (there can be no conception or reduction to practice of a new form or of a process using such a new form of an otherwise old composition where there has been no recognition or appreciation of the existence of the new form); Estee Lauder, Inc. v. L’Oreal S.A., 129 F.3d 588, 593, 44 USPQ2d 1610, 1615 (Fed. Cir. 1997) (“[W]hen testing is necessary to establish utility, there must be recognition and appreciation that the tests were successful for reduction to practice to occur.” A showing that testing was completed before the critical date, and that testing ultimately proved successful, was held insufficient to establish a reduction to practice before the critical date, since the success of the testing was not appreciated or recognized until after the critical date.); Parker v. Frilette, 462 F.2d 544, 547, 174 USPQ 321, 324 (CCPA 1972) (“[an] inventor need not understand precisely why his invention works in order to achieve an actual reduction to practice”).

V. RECOGNITION OF THE INVENTION BY ANOTHER MAY INURE TO THE BENEFIT OF THE INVENTOR

“Inurement involves a claim by an inventor that, as a matter of law, the acts of another person should accrue to the benefit of the inventor.” Cooper v. Goldfarb, 154 F.3d 1321, 1331, 47 USPQ2d 1896, 1904 (Fed. Cir. 1998). Before a non-inventor’s recognition of the utility of the invention can inure to the benefit of the inventor, the following three-prong test must be met: (1) the inventor must have conceived of the invention, (2) the inventor must have had an expectation that the embodiment tested would work for the intended purpose of the invention, and (3) the inventor must have submitted the embodiment for testing for the intended purpose of the invention. Genentech, Inc. v. Chiron Corp., 220 F.3d 1345, 1354, 55 USPQ2d 1636, 1643 (Fed. Cir. 2000). In Genentech, a non-inventor hired by the inventors to test yeast samples for the presence of the fusion protein encoded by the DNA construct of the invention recognized the growth-enhancing property of the fusion protein, but did not communicate this recognition to the inventors. The court found that because the inventors did not submit the samples for testing growth-promoting activity, the intended purpose of the invention, the third prong was not satisfied and the uncommunicated recognition of the activity of the fusion protein by the non-inventor did not inure to the benefit of the inventor. See also Cooper v. Goldfarb, 240 F.3d 1378, 1385, 57 USPQ2d 1990, 1995 (Fed. Cir. 2001) (Cooper sent to Goldfarb samples of a material for use in vascular grafts. At the time the samples were sent, Cooper was unaware of the importance of the fibril length of the material. Cooper did not at any time later convey to, or request from, Goldfarb any information regarding fibril length. Therefore, Goldfarb’s determination of the fibril lengths of the material could not inure to Cooper’s benefit.).

VI. IN AN INTERFERENCE PROCEEDING, ALL LIMITATIONS OF A COUNT MUST BE REDUCED TO PRACTICE

The device reduced to practice must include every limitation of the count. Fredkin v. Irasek, 397 F.2d 342, 158 USPQ 280, 285 (CCPA 1968); every limitation in a count is material and must be proved to establish an actual reduction to practice. Meitzner v. Corte, 537 F.2d 524, 528, 190 USPQ 407, 410 (CCPA 1976). See also Hull v. Bonis, 214 USPQ 731, 734 (Bd. Pat. Inter. 1982) (no doctrine of equivalents—remedy is a preliminary motion to amend the count to conform to the proofs).

VII. CLAIMED INVENTION IS NOT ACTUALLY REDUCED TO PRACTICE UNLESS THERE IS A KNOWN UTILITY

Utility for the invention must be known at the time of the reduction to practice. Wiesner v. Weigert, 666 F.2d 582, 588, 212 USPQ 721, 726 (CCPA 1981) (except for plant and design inventions); Azar v. Burns, 188 USPQ 601, 604 (Bd. Pat. Inter. 1975) (a composition and a method cannot be actually reduced to practice unless the composition and the product produced by the method have a practical utility); Ciric v. Flanigen, 511 F.2d 1182, 1185, 185 USPQ 103, 105-6 (CCPA 1975) (“when a count does not recite any particular utility, evidence establishing a substantial utility for any purpose is sufficient to prove a reduction to practice”; “the demonstrated similarity of ion exchange and adsorptive properties between the newly discovered zeolites and known crystalline zeolites … have established utility for the zeolites of the count”); Engelhardt v. Judd, 369 F.2d 408, 411, 151 USPQ 732, 735 (CCPA 1966) (When considering an actual reduction to practice as a bar to patentability for claims to compounds, it is sufficient to successfully demonstrate utility of the compounds in animals for somewhat different pharmaceutical purposes than those asserted in the specification for humans.); Rey-Bellet v. Engelhardt, 493 F.2d 1380, 1384, 181 USPQ 453, 455 (CCPA 1974) (Two categories of tests on laboratory animals have been considered adequate to show utility and reduction to practice: first, tests carried out to prove utility in humans where there is a satisfactory correlation between humans and animals, and second, tests carried out to prove utility for treating animals.).

VIII. A PROBABLE UTILITY MAY NOT BE SUFFICIENT TO ESTABLISH UTILITY

A probable utility does not establish a practical utility, which is established by actual testing or where the utility can be “foretold with certainty.” Bindra v. Kelly, 206 USPQ 570, 575 (Bd. Pat. Inter. 1979) (Reduction to practice was not established for an intermediate useful in the preparation of a second intermediate with a known utility in the preparation of a pharmaceutical. The record established there was a high degree of probability of a successful preparation because one skilled in the art may have been motivated, in the sense of 35 U.S.C. 103, to prepare the second intermediate from the first intermediate. However, a strong probability of utility is not sufficient to establish practical utility.); Wu v. Jucker, 167 USPQ 467, 472 (Bd. Pat. Inter. 1968) (screening test where there was an indication of possible utility is insufficient to establish practical utility). But see Nelson v. Bowler, 628 F.2d 853, 858, 206 USPQ 881, 885 (CCPA 1980) (Relevant evidence is judged as a whole for its persuasiveness in linking observed properties to suggested uses. Reasonable correlation between the two is sufficient for an actual reduction to practice.).

[Editor Note: This MPEP section has limited applicability to applications subject to examination under the first inventor to file (FITF) provisions of the AIA as set forth in 35 U.S.C. 100 (note). See MPEP § 2159 et seq. to determine whether an application is subject to examination under the FITF provisions, MPEP § 2159.03 for the conditions under which this section applies to an AIA application, and MPEP § 2150 et seq. for examination of applications subject to those provisions.]

The diligence of pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. 102(g) relates to reasonable “attorney-diligence” and “engineering-diligence” (Keizer v. Bradley, 270 F.2d 396, 397, 123 USPQ 215, 216 (CCPA 1959)), which does not require that “an inventor or his attorney … drop all other work and concentrate on the particular invention involved….” Emery v. Ronden, 188 USPQ 264, 268 (Bd. Pat. Inter. 1974).

I. CRITICAL PERIOD FOR ESTABLISHING DILIGENCE BETWEEN ONE WHO WAS FIRST TO CONCEIVE BUT LATER TO REDUCE TO PRACTICE

The critical period for diligence for a first conceiver but second reducer begins not at the time of conception of the first conceiver but just prior to the entry in the field of the party who was first to reduce to practice and continues until the first conceiver reduces to practice. Hull v. Davenport, 90 F.2d 103, 105, 33 USPQ 506, 508 (CCPA 1937) (“lack of diligence from the time of conception to the time immediately preceding the conception date of the second conceiver is not regarded as of importance except as it may have a bearing upon his subsequent acts”). What serves as the entry date into the field of a first reducer is dependent upon what is being relied on by the first reducer, e.g., conception plus reasonable diligence to reduction to practice (Fritsch v. Lin, 21 USPQ2d 1731, 1734 (Bd. Pat. App. & Inter. 1991), Emery v. Ronden, 188 USPQ 264, 268 (Bd. Pat. Inter. 1974)); an actual reduction to practice or a constructive reduction to practice by the filing of either a U.S. application (Rebstock v. Flouret, 191 USPQ 342, 345 (Bd. Pat. Inter. 1975)) or reliance upon priority under 35 U.S.C. 119 of a foreign application (Justus v. Appenzeller, 177 USPQ 332, 339 (Bd. Pat. Inter. 1971) (chain of priorities under 35 U.S.C. 119 and 120, priority under 35 U.S.C. 119 denied for failure to supply certified copy of the foreign application during pendency of the application that was filed within the twelve month period prescribed by 35 U.S.C. 119)).

II. THE ENTIRE PERIOD DURING WHICH DILIGENCE IS REQUIRED MUST BE ACCOUNTED FOR BY EITHER AFFIRMATIVE ACTS OR ACCEPTABLE EXCUSES

“A patent owner need not prove the inventor continuously exercised reasonable diligence throughout the critical period; it must show there was reasonably continuous diligence.” Perfect Surgical Techniques, Inc. v. Olympus Am., Inc., 841 F.3d 1004, 1009, 120 USPQ2d 1605, 1609 (Fed. Cir. 2016) (emphasis in original) (citing Tyco Healthcare Grp. v. Ethicon EndoSurgery, Inc., 774 F.3d 968, 975, 112 USPQ2d 1979 (Fed. Cir. 2014) and Monsanto Co. v. Mycogen Plant Sci., Inc., 261 F.3d 1356, 1370, 59 USPQ2d 1930, 1939 (Fed. Cir. 2001)).

An inventor must account for the entire period during which diligence is required. Gould v. Schawlow, 363 F.2d 908, 919, 150 USPQ 634, 643 (CCPA 1966) (Merely stating that there were no weeks or months that the invention was not worked on is not enough.); In re Harry, 333 F.2d 920, 923, 142 USPQ 164, 166 (CCPA 1964) (statement that the subject matter “was diligently reduced to practice” is not a showing but a mere pleading). A 2-day period lacking activity has been held to be fatal. In re Mulder, 716 F.2d 1542, 1545, 219 USPQ 189, 193 (Fed. Cir. 1983) (37 CFR 1.131 issue); Fitzgerald v. Arbib, 268 F.2d 763, 766, 122 USPQ 530, 532 (CCPA 1959) (Less than 1 month of inactivity during the critical period shows a lack of diligence. Efforts to exploit an invention commercially do not constitute diligence in reducing it to practice. An actual reduction to practice in the case of a design for a three-dimensional article requires that it should be embodied in some structure other than a mere drawing.); Kendall v. Searles, 173 F.2d 986, 993, 81 USPQ 363, 369 (CCPA 1949) (Evidence of diligence must be specific as to dates and facts.).

The period during which diligence is required must be accounted for by either affirmative acts or acceptable excuses. Rebstock v. Flouret, 191 USPQ 342, 345 (Bd. Pat. Inter. 1975); Rieser v. Williams, 225 F.2d 419, 423, 118 USPQ 96, 100 (CCPA 1958) (Being last to reduce to practice, party cannot prevail unless he has shown that he was first to conceive and that he exercised reasonable diligence during the critical period from just prior to opponent’s entry into the field); Griffith v. Kanamaru, 816 F.2d 624, 2 USPQ2d 1361 (Fed. Cir. 1987) (Court generally reviewed cases on excuses for inactivity including vacation extended by ill health and daily job demands, and held lack of university funding and personnel are not acceptable excuses.); Litchfield v. Eigen, 535 F.2d 72, 190 USPQ 113 (CCPA 1976) (budgetary limits and availability of animals for testing not sufficiently described); Morway v. Bondi, 203 F.2d 741, 749, 97 USPQ 318, 323 (CCPA 1953) (voluntarily laying aside inventive concept in pursuit of other projects is generally not an acceptable excuse although there may be circumstances creating exceptions); Anderson v. Crowther, 152 USPQ 504, 512 (Bd. Pat. Inter. 1965) (preparation of routine periodic reports covering all accomplishments of the laboratory insufficient to show diligence); Wu v. Jucker, 167 USPQ 467, 472-73 (Bd. Pat. Inter. 1968) (applicant improperly allowed test data sheets to accumulate to a sufficient amount to justify interfering with equipment then in use on another project); Tucker v. Natta, 171 USPQ 494,498 (Bd. Pat. Inter. 1971) (“[a]ctivity directed toward the reduction to practice of a genus does not establish, prima facie, diligence toward the reduction to practice of a species embraced by said genus”); Justus v. Appenzeller, 177 USPQ 332, 340-1 (Bd. Pat. Inter. 1971) (Although it is possible that patentee could have reduced the invention to practice in a shorter time by relying on stock items rather than by designing a particular piece of hardware, patentee exercised reasonable diligence to secure the required hardware to actually reduce the invention to practice. “[I]n deciding the question of diligence it is immaterial that the inventor may not have taken the expeditious course….”).

Examiners should weigh the body of evidence to make the determination of whether there was reasonably continuous diligence for the entire critical period. This determination should be made with the purpose of the diligence requirement in mind, which “is to assure that, in light of the evidence as a whole, ‘the invention as not abandoned or unreasonably delayed.’” Perfect Surgical Techniques, Inc. v. Olympus Am., Inc. (Perfect Surgical), 841 F.3d 1004, 1009, 120 USPQ2d 1605, 1609 (Fed. Cir. 2016) (citations omitted). In Perfect Surgical, the Federal Circuit stated:

Under this standard, an inventor is not required to work on reducing his invention to practice every day during the critical period. … And periods of inactivity within the critical period do not automatically vanquish a patent owner's claim of reasonable diligence…. In determining whether an invention antedates another, the point of the diligence analysis is not to scour the patent owner's corroborating evidence in search of intervals of time where the patent owner has failed to substantiate some sort of activity. It is to assure that, in light of the evidence as a whole, “the invention was not abandoned or unreasonably delayed.” . That an inventor overseeing a study did not record its progress on a daily, weekly, or even monthly basis does not mean the inventor necessarily abandoned his invention or unreasonably delayed it. The same logic applies to the preparation of a patent application: the absence of evidence that an inventor and his attorney revised or discussed the application on a daily basis is alone insufficient to determine that the invention was abandoned or unreasonably delayed. One must weigh the collection of evidence over the entire critical period to make such a determination.

Our decision in In re Mulder, 716 F.2d 1542, 1542-46 [219 USPQ 189] (Fed. Cir. 1983), does not instruct otherwise. The Board cites In re Mulder for the proposition that “[e]ven a short period of unexplained inactivity may be sufficient to defeat a claim of diligence.” …. In In re Mulder, a competing reference was published just days before the patent at issue was constructively reduced to practice. …. The patent owner was tasked with showing reasonable diligence during a critical period lasting only two days. . But the patent owner did not produce any evidence of diligence during the critical period. . Nor could it point to any activity during the months between the drafting of the application and the start of the critical period. . Although the critical period spanned just two days, we declined to excuse the patent owner's complete lack of evidence. . In re Mulder does not hold that an inventor's inactivity during a portion of the critical period can, without more, destroy a patent owner's claim of diligence.

Perfect Surgical, 841 F.3d at 1009, 120 USPQ2d at 1609 (citations omitted).

III. WORK RELIED UPON TO SHOW REASONABLE DILIGENCE MUST BE DIRECTLY RELATED TO THE REDUCTION TO PRACTICE

The work relied upon to show reasonable diligence must be directly related to the reduction to practice of the invention in issue. Naber v. Cricchi, 567 F.2d 382, 384, 196 USPQ 294, 296 (CCPA 1977), cert. denied, 439 U.S. 826 (1978). See also Scott v. Koyama, 281 F.3d 1243, 1248-49, 61 USPQ2d 1856, 1859 (Fed. Cir. 2002) (Activities directed at building a plant to practice the claimed process of producing tetrafluoroethane on a large scale constituted efforts toward actual reduction to practice, and thus were evidence of diligence. The court distinguished cases where diligence was not found because inventors either discontinued development or failed to complete the invention while pursuing financing or other commercial activity.); In re Jolley, 308 F.3d 1317, 1326-27, 64 USPQ2d 1901, 1908-09 (Fed. Cir. 2002) (diligence found based on research and procurement activities related to the subject matter of the interference count). “[U]nder some circumstances an inventor should also be able to rely on work on closely related inventions as support for diligence toward the reduction to practice on an invention in issue.” Ginos v. Nedelec, 220 USPQ 831, 836 (Bd. Pat. Inter. 1983) (work on other closely related compounds that were considered to be part of the same invention and which were included as part of a grandparent application). “The work relied upon must be directed to attaining a reduction to practice of the subject matter of the counts. It is not sufficient that the activity relied on concerns related subject matter.” Gunn v. Bosch, 181 USPQ 758, 761 (Bd. Pat. Inter. 1973) (An actual reduction to practice of the invention at issue which occurred when the inventor was working on a different invention “was fortuitous, and not the result of a continuous intent or effort to reduce to practice the invention here in issue. Such fortuitousness is inconsistent with the exercise of diligence toward reduction to practice of that invention.” 181 USPQ at 761. Furthermore, evidence drawn towards work on improvement of samples or specimens generally already in use at the time of conception that are but one element of the oscillator circuit of the count does not show diligence towards the construction and testing of the overall combination.); Broos v. Barton, 142 F.2d 690, 691, 61 USPQ 447, 448 (CCPA 1944) (preparation of application in U.S. for foreign filing constitutes diligence); De Solms v. Schoenwald, 15 USPQ2d 1507 (Bd. Pat. App. & Inter. 1990) (principles of diligence must be given to inventor’s circumstances including skill and time; requirement of corroboration applies only to testimony of inventor); Huelster v. Reiter, 168 F.2d 542, 78 USPQ 82 (CCPA 1948) (an inventor who was not able to make an actual reduction to practice of the invention, must also show why constructive reduction to practice by filing an application was not possible).

IV. DILIGENCE REQUIRED IN PREPARING AND FILING PATENT APPLICATION

The diligence of an attorney in preparing and filing patent application inures to the benefit of the inventor. Conception was established at least as early as the date a draft of a patent application was finished by a patent attorney on behalf of the inventor. Conception is less a matter of signature than it is one of disclosure. An attorney does not prepare a patent application on behalf of particular named persons, but on behalf of the true inventive entity. Six days to execute and file application is acceptable. Haskell v. Coleburne, 671 F.2d 1362, 213 USPQ 192, 195 (CCPA 1982). See also Bey v. Kollonitsch, 806 F.2d 1024, 231 USPQ 967 (Fed. Cir. 1986) (Reasonable diligence is all that is required of the attorney. Reasonable diligence is established if the attorney worked reasonably hard on the application during the continuous critical period. If the attorney has a reasonable backlog of unrelated cases which the attorney takes up in chronological order and carries out expeditiously, that is sufficient. Work on a related case(s) that contributed substantially to the ultimate preparation of an application can be credited as diligence.). In “the preparation" of a patent application, "the absence of evidence that an inventor and his attorney revised or discussed the application on a daily basis is alone insufficient to determine that the invention was abandoned or unreasonably delayed." Perfect Surgical Techniques, Inc. v. Olympus Am., Inc., 841 F.3d 1004, 1009, 120 USPQ2d 1605, 1609 (Fed. Cir. 2016).

V. END OF DILIGENCE PERIOD IS MARKED BY EITHER ACTUAL OR CONSTRUCTIVE REDUCTION TO PRACTICE

“[I]t is of no moment that the end of that period [for diligence] is fixed by a constructive, rather than an actual, reduction to practice.” Justus v. Appenzeller, 177 USPQ 332, 340-41 (Bd. Pat. Inter. 1971).